INTRODUCTION

The dispute regarding junior doctors’ contracts stretches as far back as 2012. At that time, the Department of Health (DOH) decided that the terms and conditions of employment for the 53,000 junior doctors in England needed to be revised for two main reasons. Firstly, the contracts had not been updated since the late 1990s. Secondly, the idea of a 7-day NHS was being suggested and the DOH proposed a major reconfiguration of junior doctors’ work patterns to fit with this new model. Official negotiations between the British Medical Association (BMA) and the DOH began in October 2013, but after almost 2 years, no consensus was reached. In August 2015, the Junior Doctor’s Committee of the BMA decided not to re-enter negotiations and accused the government of taking a ‘heavy-handed approach’. Ministers then stated that they intended to impose the new contract on all junior doctors from August 2016 – triggering the current wave of protests and the proposed industrial action.

Although the issues surrounding the fine details of the contract are complex, junior doctors’ concerns boil down to two major objections. Firstly, we are very concerned that the proposed contract is NOT SAFE and will put patients at significant risk by stretching the resources of an already strained system beyond breaking point. Secondly, we are distraught over the fact that the proposed contract is also NOT FAIR and will decimate morale and working conditions through for example, the removal of remuneration guarantees and safety restrictions relating to out-of-hours work.

The official declaration from the BMA states:

“We urge the government not to impose a contract that is unsafe and unfair. We will resist a contract that is bad for patients, bad for junior doctors and bad for the NHS.”

WHY THE PROPOSALS ARE NOT SAFE

- The proposals are based upon the misinterpretation of mortality statistics

When explaining the rationale behind a 7-day NHS, Jeremy Hunt most often quotes a study from 2012 by Freemantle and colleagues published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. This study suggests that people admitted to hospital at the weekend are at increased risk of dying in the 30 days following their admission. Based on statistical modelling, the paper suggests that there may be around 11,000 excess deaths due to what they term ‘the weekend effect’. A direct quote from the paper’s conclusion states:

“It may be that reorganized services providing 7-day access to all aspects of care could improve outcomes for higher risk patients currently admitted at the weekend. However, the economics for such a change need further evaluation to ensure that such reorganization represents an efficient use of scarce resources.”

Essentially, the conclusion is that extending ‘all aspects of care’ – which would include elements such as laboratory facilities; imaging services; allied health professionals etc might reduce some of these deaths. Jeremy Hunt however has repeatedly asserted, as in the quote below, that increasing the number of doctors at weekends is the key to reducing this excess mortality. There is no evidence that this measure alone will address the issue of excess mortality and there are no plans for an associated expansion of ‘all aspects of care’.

“What we do need to change are the excessive overtime rates that are paid at weekends that give hospitals a disincentive to roster as many junior doctors as they need at the weekend which leads to those 11,000 excess deaths.”

Jeremy Hunt, Questions in the House of Commons 13th October 2015

We have highlighted over and over again through campaigns such as #iminworkjeremy that there is no change in the number of junior doctors staffing acute services at the weekend. The BMA, shadow health secretary, DOH and members of the conservative party, have all tried to gain an understanding during negotiations as to why Mr. Hunt is misrepresenting the data and focussing excessively on junior doctors, but answers have not been forthcoming.

“I am unclear how a new junior doctor contract that will cut the pay of doctors entering GP training, cut the pay of psychiatry registrars…..and cut the pay of A&E doctors, will help deliver a seven-day service.”

Dan Poulter, Conservative MP and Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in Department of Health until May 2015. Writing in ‘The Guardian’ 4th October 2015

- The DDRB proposals will remove regulations on unsafe working patterns

Based on this opaque and confusing interpretation of the data, the government asked the DDRB (Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration Review Body) to consider all ‘evidence’ relating to contract negotiations for junior doctors and consultants in England. The DDRB are a group comprised of government selected reviewers with no background in healthcare. They were asked to make recommendations by July 2015.

One of the main recommendations that emerged in the DDRB report, which is in keeping with Mr Hunt’s misinterpretation of the evidence, is for a change in the definition of what constitutes out-of-hours’ work for a junior doctor. The aim of these changes is to allow hospitals to rota junior doctors to work extra, unregulated, unsocial hours without an increase in pay or rest periods. At the moment, junior doctors are paid ‘standard’ time during normal working hours, which are defined as 7am-7pm Monday to Friday. In the proposed amendments, ‘standard’ time will be extended from 60 hours to 90 hours per week and stretch up to 10pm every night of the week apart from Sunday. Essentially, this will classify antisocial hours such as 9pm on a Saturday within the same bracket as say 2pm on a Wednesday.

Crucially, the current system also has built in safeguards to prevent employers from forcing doctors to work excessive hours and to ensure that they receive adequate breaks. These safeguards were introduced, in large part as patient safety measures so that people were not being seen and treated by doctors who were exhausted and overworked. There is no alternative system proposed either within the DDRB report or by the DOH, to protect junior doctors from unsafe working conditions or to protect patients from the consequences of these. We are gravely concerned that this loss of safeguards may see a return to the ‘bad old days’ were junior doctors worked for 100+ hours per week and patients suffered as a result.

“If you assume that we’re just about coping in the five days that we’re working now, you will need another two days’ worth [of doctors]. You’re asking for two days’ more work out of people.”

Jane Dacre, President of the Royal College of Physicians, ‘The Guardian’ 13th October 2015

- Hunt’s proposals are ‘Rash and Misleading’

In September 2015, Freemantle and colleagues published a follow-up to their original weekend mortality study in the British Medical Journal. The authors do not explicitly state that the new study is partially a response to Mr. Hunt’s misuse of their statistics, but contained within the paper are a number of thinly veiled rebuttals of Mr. Hunt’s misinterpretations:

With regards to the excess weekend mortality that Mr. Hunt is constantly referring to:

“It is not possible to ascertain the extent to which these excess deaths may be preventable; to assume that they are avoidable would be rash and misleading”

With regards to the measures that may reduce the excess mortality:

“Appropriate support services in hospitals are usually reduced from Late Friday through the weekend, leading to disruption on Monday morning. This could go some way towards explaining our findings of a ‘weekend effect’”.

Mr. Hunt has repeatedly stated, with great certainty, that the deaths can be avoided by increased antisocial hours work by junior doctors – a rash and misleading assertion that is not grounded in evidence. In recent days, the editor of the British Medical Journal has written to Mr. Hunt personally to express her concerns about his misuse of her journal’s published data.

“I am writing to register my concern about the way in which you have publicly misrepresented an academic article published in The BMJ.”

“What [the paper] does not do is apportion any cause for [the excess mortality], nor does it take a view on what proportion of those deaths might be avoidable,”

From Fiona Godlee’s Letter to Jeremy Hunt 21st October 2015

- The NHS cannot afford a 7-day service in the current funding climate

In discussing the economics of a 7-day comprehensive service, Freemantle and colleagues state:

“The economics for such a change need further evaluation to ensure that such reorganization represents an efficient use of scarce resources.”

The NHS is at present facing a funding crisis. There is already a £930 million deficit from just the first 3 months of this financial year, with a likely £2 billion deficit predicted by the end of the financial year. Since its inception, up until 2010, the NHS received a 4% real terms increase in funding year on year. This allowed the service to expand and keep up with the proliferation of complex medical interventions needed to treat a growing and ageing population afflicted by increasingly complex medical problems. Since 2010, the average annual increase in funding has been just 0.4%. This is in spite of vast bodies of international evidence stating that during times of economic austerity, sustained health expenditure is crucial, both to prevent excess mortality and to support economic growth by maintaining the health of the workforce.

A true 7-day NHS where ‘all aspects of care’ are expanded is currently well beyond the realms of affordability, unless the current government allocates a significant amount of financial resources to the NHS. The excessive focus on junior doctors has been a major distractor from this fundamental issue.

WHY THE PROPOSALS ARE NOT FAIR

- Extension of ‘standard time’ and ending banding payments will see junior doctors receiving up to 30% less pay

Junior doctors routinely work outside of the current ‘standard time’ and are happy to do so to provide their patients with high quality care around the clock. Currently, if junior doctors work outside these hours they receive a pay premium reflecting the impact of unsocial hours on personal and family life. The changes to routine working hours will result in junior doctors working what are widely classified as antisocial hours, with no pay premium. Evenings and weekends are precious opportunities to spend time with friends and family and we feel that it is only fair that pay during those times reflects this.

Furthermore, the DDRB have proposed that the current ‘banding system’, which provides junior doctors with pay supplements based on an overall assessment of the length and unsocial timings of their duties, will be removed and with them safeguards (discussed above) to prevent junior doctors working excessive hours. A simpler alternative to the banding system was broadly supported by junior doctors. However, due to the extension of ‘standard time’ the current proposals will disproportionately impact pay in specialties that have particularly heavy out-of-hours commitments such as Anaesthetics and A&E. We are very concerned that this will further dis-incentivise people from training in these specialities, some of which are already significantly under-staffed.

By extending ‘standard time’ and removing the ‘banding system’, some junior doctors stand to lose up to 30% of their salary, effectively overnight.

- Pay progression will disadvantage junior doctors who take time out due to sickness, maternity leave or to undertake research

Under the current contract, junior doctors’ pay increases every year in recognition of experience gained. The new contract will remove this, and accumulated pay progressions. Pay will only rise upon progression to higher stages of training (there is no clear plan from the DOH as to how exactly this will work). This change will disadvantage those who take time out of training, for example because of maternity leave or sickness, or to train less-than-full-time. Such doctors may lose years of accumulated pay and take significantly longer to progress up the pay scales. This is a change which would particularly affect women. It would also negatively impact those taking time out to undertake research. Pay progression should recognise the increase in valuable experience that comes with spending time in training, working and researching. No one should be put off training in medicine because of their gender or personal circumstances.

“Removal of annual pay progression and its replacement with pay increases only at points of responsibility is potentially discriminatory for less than full time trainees as they will be exposed to a greater financial risk because of the delay they will inevitably experience in reaching their responsibility thresholds.”

Extract from an Open Letter to Junior Doctors from the Royal College of Pediatrics & Child Health in response to the proposed changes to the Junior Doctors’ contract

“Plans to remove the GP trainee supplement, which ensures they have pay parity with hospital trainees, would see a reduction in their pay of around a third.”

From the BMA Analysis of DDRB recommendations.

- Changes to pay protection may result in inequalities in pay

Currently, junior doctors who choose to retrain in a different specialty have their pay protected and pay continues to increase annually as per the pay progression described above. However, under the new contract, retraining in a different specialty will result in a lower salary by default, with only the possibility of some form of pay premium (again the details of this are not clear) for certain trainees to recognise the usefulness of their experience. The value of such premiums will be determined by employers. In addition, pay may not be protected for junior doctors who take time out of training – for example to undertake aid work. Again, there is only the possibility of a pay premium for reasons deemed to be valuable by employers. This could result in inequalities in pay for doctors of equal experience across the country.Recruitment and retention problems may also be exacerbated by the removal of pay protection, as it would dis-incentivise any doctor wishing to train in another specialty.

“The removal of annual increments from those taking time “out of programme”, for example for research training, other additional experience, or parental leave, is damaging to our attempts to promote growth and excellence in paediatric academia, and family-friendly working for mothers and fathers.”

Extract from an Open Letter to Junior Doctors from the Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health in response to the proposed changes to the Junior Doctors’ contract.

CONCLUSION

If a doctor were to intentionally distort the interpretation of clinical risk data and seriously compromise patient safety, there is a very good chance that they would lose their license to practice and could possibly face criminal charges. Many doctors believe that Mr. Hunt should be held to the same standards. A letter, co-signed by thousands of doctors and medical students has been sent to the Cabinet Office requesting that they investigate whether Mr. Hunt has indeed breached the ministerial code of conduct:

“It appears Mr. Hunt deliberately and knowingly misquoted and misinterpreted the conclusions of a medical research publication in an attempt to mislead the other Members of Parliament and the UK public.”

From a letter to the Cabinet office outlined by Dr Antonio de Marvao and Dr Palak J Trivedi

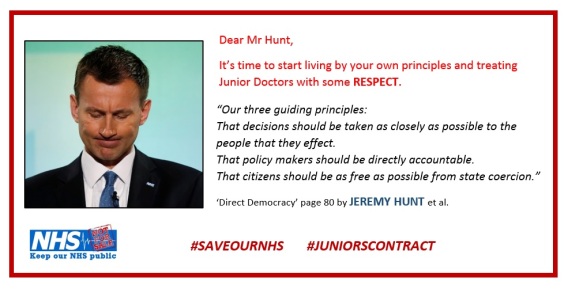

We want to believe that the government has the best interests of the health service at heart. However, when we consider the situation across the NHS as a whole it is difficult to ignore the pattern that emerges. The system is under severe strain from chronic governmental neglect in terms of a lack of sustained funding increases. The system is becoming increasingly fragmented as a result of major reorganisations (Health and Social Care Act). There have been major cuts in social care provision forcing the NHS to take up the slack. On the back of all this, comes an attempt to destroy the working conditions of one of the major groups of NHS service providers. In light of all this, many of us have been very disturbed to read the quotes from the book that Mr. Hunt co-authored in which he outlines his opinions on the NHS.

“Our ambition should be to break down the barriers between private and public provision, in effect DENATIONALISING the provision of health care in Britain.”

From ‘Direct Democracy’ by Jeremy Hunt et al

Taking all of this into account, it is hard to imagine that the aim of the current government is anything other than the gradual destabilization and deconstruction of the NHS. Once the system is beyond repair, conditions will be perfect for ushering in a new era of widespread service privatization. The Health and Social Care Act has ensured that there are no solid constitutional safeguards to stop this from happening.

This brings us to the issue of industrial action. The idea of a strike makes many doctors deeply uncomfortable. In light of this, the overwhelming support for strike action demonstrates just how important we consider these issues to be. This is not just a fight for doctors pay and conditions but for the survival of the NHS as a whole. A lot of work is being undertaken by the BMA and doctor’s groups to look at the international evidence surrounding strike action to ensure that any strike is as effective as possible without putting patients at risk.

Doctors will be balloted regarding industrial action from the 5th November. The BMA wants the following concrete assurances in writing from the Government before it feels able to re-enter negotiations:

- Proper recognition of unsocial hours as premium time

- No disadvantage for those working unsocial hours compared to current system

- No disadvantage for those working less than full time and taking parental leave compared to the current system

- Pay for all work done

- Proper hours safeguards protecting patients and their doctors

This article is taken from the Yorkshire & Humber Junior Doctors’ Protest Group Press Release: @yhdoctors

d changes to junior doctors’ contracts will affect patient safety. For example, there can be no doubt, that especially in the immediate wake of any imposed changes, there will be significantly elevated levels of occupational stress for many junior doctors, as they carry with them to work their feelings of disenfranchisement heaped upon worries about loss of pay and extended antisocial hours. The myriad ways in which stress erodes the ability of both individuals and teams to deal with complex situations has been very well researched, in multiple settings, including healthcare environments.

d changes to junior doctors’ contracts will affect patient safety. For example, there can be no doubt, that especially in the immediate wake of any imposed changes, there will be significantly elevated levels of occupational stress for many junior doctors, as they carry with them to work their feelings of disenfranchisement heaped upon worries about loss of pay and extended antisocial hours. The myriad ways in which stress erodes the ability of both individuals and teams to deal with complex situations has been very well researched, in multiple settings, including healthcare environments.